This is part two of my series on Social Determinism Theory, and covers the category of ‘Relatedness’. You can read part one on Competence here.

As a reminder, SDT is a theory of motivation and identifies three innate needs that, if satisfied, allow optimal function and growth:

Competence

Seek to control the outcome and experience master

Relatedness

Is the universal want to interact, be connected to, and experience caring for others

Autonomy

Is the universal urge to be causal agents of one’s own life and act in harmony with one’s integrated self; however, Deci and Vansteenkiste note this does not mean to be independent of others

Act II: Relatedness

“The universal want to interact, be connected to, and experience caring for others”.

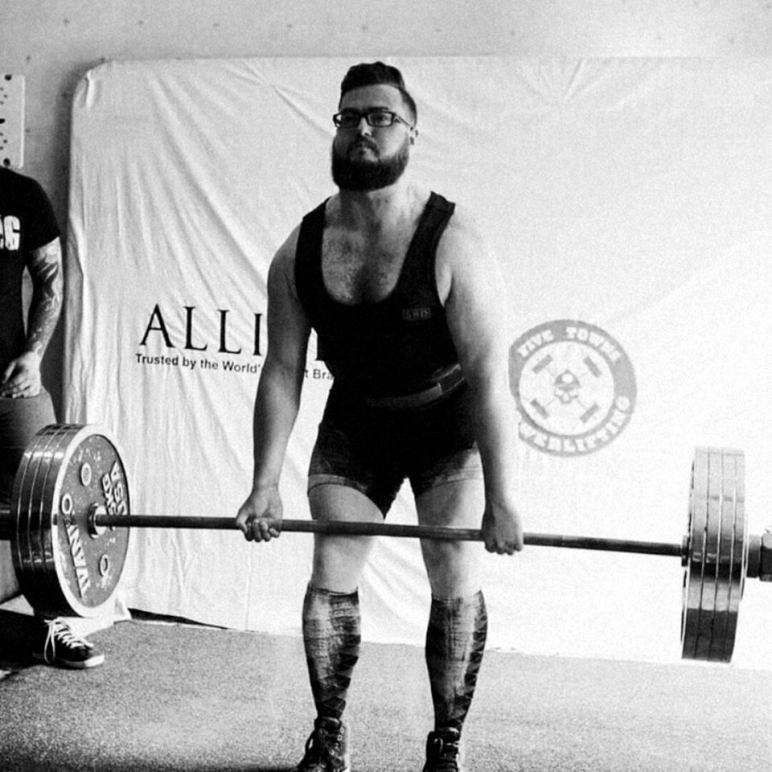

That’s almost a pec

That’s almost a pec

The need for relatedness is defined as individuals’ inherent propensity to feel connected to others, that is, to be a member of a group, to love and care and be loved and cared for (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). The need for relatedness is satisfied when people experience a sense of communion and develop close and intimate relationships with others (Deci & Ryan, 2000). The assumption that individuals have the natural tendency to integrate themselves in the social matrix and benefit from being cared for is equally emphasized in developmental approaches such as Attachment Theory (Bowlby, 1969). It is consistent with concepts in organizational psychology such as social support (Viswesvaran, Sanchez, & Fisher, 1999)

In the context of powerlifting, we can use relatedness pretty much to mean having others to give a shit about your training and progress, and to reciprocate that. One of the best things I ever did for my powerlifting progress was joining West Riding Powerlifters.

If an article doesn’t feature a pic of Boris it’s not worth reading

If an article doesn’t feature a pic of Boris it’s not worth reading

As mentioned, relatedness is related (lol) to ‘Social Support’ theory. Social support is basically the perception and actuality that one is cared for, has assistance there if needed from others and belonging within a supportive social network. These support resources can be emotional (like nurturing a competitive mindset), informational (like explaining the science behind a programming decision), companionship (being a club/team mate), tangible (like lending someone equipment) or intangible (like offering personal advice such as “wash your knee sleeves”).

The below is from this page and I can’t be arsed to reword it just to make you think I’ve come up with something that sounds smart;

“Psychology literature had shown that the perception of available support can be a better predictor of health or well-being outcomes (Sarason, Pierce, & Sarason, 1990) ; researchers in sport psychology had also focused more on the perception of available support, which is called perceived support. It was shown that perceived support plays a significant role both for sport performance ( Rees & Freeman, 2010; Rees & Freeman, 2007) and psychological health outcomes, such as low levels of burnout (Tsuchiya, 2012) . As such, perceived support was commonly measured in research examining social support within a sport context.

In addition, to the perception of social support, more recently, researchers have moved their focus onto social support actually exchanged, which is called received support. Received support is defined as the actual receipt of social support reported by a recipient (Rees, 2007) . Received support has been reported, mostly in the interviews with athletes, as a significant factor in athletes’ self-confidence (Hays, Maynard, Thomas, & Bawden, 2007) , performance improvement (Rees & Freeman, 2010) , in dealing with negative psychological states due to injury in sport (Carson & Poleman, 2012) , competitive stressors (Weston, Thelwell, Bond, & Hutching, 2009) , and organizational stressors (Kristiansen & Roberts, 2010) .”

So how do we implement this?

You need to find your tribe.

I’m at least 50% responsible for this.

I’m at least 50% responsible for this.

Join a gym where you’re not the strongest person, stuck in a corner apologising for using chalk and making noise. Even if you’re stuck in a commercial or bodybuilding gym, you can find people who have passion for making progress – make them your peers in the gym, even if they aren’t powerlifters. If there’s a group of people all training with a similar goal in your gym, make it formal and start a club. If you’re on different schedules get together once a week, fortnight or even monthly and train together. Get yourself around people who care about your goals and whose goals you care about.

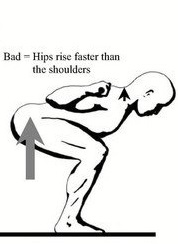

We all know one of these.

We all know one of these.

If you don’t have the opportunity to join a club, find a space online that cares. Our WRPL Facebook group is a good space for powerlifting banter, and Reddit’s r/powerlifting is also a nice place to start. Eat, Train, Progress is an excellent Facebook group full of people with lots of different goals, but who all care about fostering a supportive environment.

There are plenty of online spaces where you can find a community that you can be a part of and these are just a couple suggestions from my personal experience.

If you’re reading this as a coach, then it shouldn’t need saying that your athletes need to know you care about them. You need to be there for more than just prescribing setsxrepsxload. I know it can be time consuming but if a lifter is reaching out to you very often, especially for what appears to be trivial issues, consider that they may be needing to feel more supported in their journey, and just letting them know you’ve got their back and you’re proud of them can go a very long way.

Lifters, make sure you’re allowing yourself to build that relationship with your coach, don’t be afraid to be a little vulnerable and open yourself up when you need the support. Being a coachable athlete goes well beyond just doing your sets and hitting your macros, it’s very hard to get the most out of a closed book.

The most important thing here is to find yourself a community, even if you have to build it from the ground up. Again the majority of these suggestions are very obvious things you’ve probably considered already. The point here is to reflect on what you can do to make improvements; sometimes a tiny change has exponential returns. If you feel like you’d like more support in your powerlifting journey then Get in Touch.

This is not my happy place

This is not my happy place Sometimes I dream about banging your mum.

Sometimes I dream about banging your mum. please adopt me

please adopt me aka ‘The Caine Method’

aka ‘The Caine Method’ Please get in touch for my ‘Photoshop Mastery’ course.

Please get in touch for my ‘Photoshop Mastery’ course. Lovingly borrowed from MASS Issue 5. You should

Lovingly borrowed from MASS Issue 5. You should  #bulkingnotsulking

#bulkingnotsulking “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler” – Albert Einstein

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler” – Albert Einstein Swole and Shreksy

Swole and Shreksy